Go to Whole Earth Collection Index

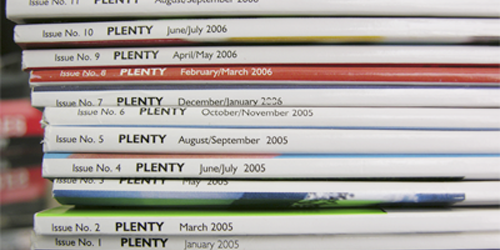

by Steven Kotler. This article originally appeared in Plenty magazine (November 2008)

In the opening pages of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe describes "a thin blond guy with a blazing disk on his forehead," wearing "just an Indian bead necklace on bare skin and a white butcher's coat with medals from the King of Sweden on it." This guy is Stewart Brand, a Stanford-educated biologist and an ex–Army paratrooper turned Ken Kesey cohort and fellow merry prankster who, in 1966, at age 28, had launched a nationwide campaign to convince NASA to release for the first time a photo of the entire planet taken from space. (He made buttons reading "Why Haven't We Seen a Photograph of the Whole Earth Yet?" and hitchhiked around the country selling them.) A few months after Wolfe's book was published, in March 1968, Brand was flying back to California from his father's funeral in Nebraska. He was reading a copy of Barbara Ward's Spaceship Earth and trying to answer a pair of questions: How can I help all my friends who are currently moving back to the land? And, more important, how can I help save the planet?

While on that flight, Brand came up with a solution: to publish a magazine in the vein of the LL Bean catalog - which he'd always admired for its immense practicality - that would blend liberal social values with emerging ideas about "appropriate technology" and "whole-systems thinking." He decided to run NASA's photograph of the planet on the cover and to call the publication the Whole Earth Catalog (WEC). The first WEC, published in July 1968, was a six-page mimeograph that began with Brand’s now-legendary statement of purpose: "We are as gods and we might as well get good at it."

The WEC lasted four years (along with some special editions since). During that time, the magazine published a flood of articles about species preservation, organic farming, and alternative energy - but it was also a resource for "tools" as wide ranging as Buddhist economics, nanotechnology, and a manure-powered generator. Comprehensive in this way, the WEC was a catalyst, helping transform a set of disparate individualists into a potent community. As Lloyd Kahn, the catalog's shelter editor, says, "The beatniks had a negative, existential vibe. They weren't into sharing. But the hippies came along and wanted to share everything. Whatever they discovered, they just wanted to broadcast. The WEC was the very best example of this."

It is now 40 years later and the WEC's avalanche of influence continues to flow. Cyberculture, the blogosphere, companies like Apple and Patagonia, websites like Craigslist and worldchanging.org, sustainable building, ethical business practices, and the gamut of alternative-energy industries were all shaped by its pages. Its ecological legacy spans everything from new cattle-grazing techniques to major environmental legislation. What follows is an oral history, compiled from 30 hours of interviews, that takes a look at the Whole Earth Effect - the long-lasting impact of this short-lived journal, as told by the people directly in its path.

Stewart Brand: The line from Kesey and the Pranksters to WEC is pretty clear: They were lower–middle class guys, and lower–middle class guys like tools. We were always messing around with gear or drug apparatus or whatever. So the whole DIY frame of reference molded into the WEC.

Huey Johnson: San Francisco in the ’60s was where all the square pegs wound up. All the super-bright people from Milwaukee and Detroit and such brought all their bright ideas with them - on the environment, new technology, whole-systems thinking. And the WEC was the place where most of these new ideas ended up.

John Markoff: WEC was paperback hypertext. Everyone who was part of the culture back then used it as a reference point. It was a portable library about everything and anything that was interesting and important and, often, unnoticed. That was Brand's gift: Whatever the topic, he was always the first person to get it.

Steve Jobs: The WEC ... was sort of like Google in paperback form, 35 years before Google came along. It was idealistic and overflowing with neat tools and great notions.

Jay Baldwin: Stewart Brand came to me because he heard that I read catalogs. He said, "I want to make this thing called Whole Earth Catalog so that anyone on the planet can pick up a telephone and find out the complete information on anything."

Peter Coyote: For the entire back-to-the-land movement, the WEC was an encyclopedia of technology and skills. It was all the stuff you needed to know but didn't know where to learn.

Andrew Kirk: Brand embraced technology. The satellite photo on the WEC cover was the best example. It was true genius, the fundamental insight for the environmental movement - seeing the earth from space, people instantly know how finite our resources are. And Brand realized that at a time when most of his peers hated the space program because it was "big science."

John Perry Barlow: William Gibson said, "The street finds its own use for things," and the WEC was the street. Brand wanted NASA to give the world a picture of itself, then he widely distributed that picture. It changed the street - that photo got the entire culture thinking about the ecology of human endeavor.

Larry Peterson: The fear was that we were having an energy crisis that could set us back to the 1940s, to a time when all we could afford was one bare lightbulb to hang in the kitchen. But Brand and others at the WEC were into stuff that seems cutting edge today: solar power, recycling, and wind energy. They realized that reducing the amount of energy we were using didn't mean going backward, and this was new thinking.

Jay Baldwin: We had to drive to work, and that always bothered me. Sure, I drove the world's most minimal car, a Citroën 2CV, but I still had to drive it. This was problematic. Everyone at the WEC attempted to live as they wrote. When we decided to advocate for solar power and heating, we first tried to live by it at 8,000 feet, in New Mexico, where the winter temperatures dropped to -20°C.

Andrew Kirk: As governor, Jerry Brown was interested in cutting-edge ideas and the WEC was San Francisco's intelligentsia. Pretty soon WEC staffers got very active in California politics. Because of this, California became the nation's laboratory for reconciling environmental issues with a thriving economic culture. For example, when Peter Warshall used an environmental impact statement to help save the town of Bolinas from encroaching suburban sprawl, it was the first time that had been done - but it wasn't the last.

Huey Johnson: We saved 1,200 miles of California rivers with an environmental impact statement. We used it to pass the Wild Rivers Act. See, both the federal government and the state of California had passed the bill, but for it to become law someone had to marry the two. All of California's water interests were doing everything they could to make sure it didn't happen. Plus, Carter was leaving office in a few months and Reagan was coming in - and there was no way he would let it happen. But I had this black gal in my office named Vera Marcus. She was tough, always walking up to me saying, "Hey, white boy, why don't you challenge me?" So I gave her the Wild Rivers project. She did the impossible: She got an environmental impact statement done in four months. That's two years' worth of work. Signing the Wild Rivers Act into law was the very last thing that the Carter Administration did in office.

Vera Marcus: I don't know if I was the first African-American in the environmental movement, but it's a pretty good bet that I was the first African-American woman to hold a position of real power. After Johnson made me assistant secretary for resources, I started attending meetings and all the environmental folks got upset. They would say, "They had to send a black woman - don't we have enough problems already?" I think they stopped saying that when I got the job done.

Huey Johnson: The WEC techies made that bill possible, too. For it to get finished, we needed all of these signatures from people all over the country. So the WEC guys showed up with this massive, magical box. You put paper in one end and it came out somewhere else. It was this amazing machine called a fax. It's a good thing Brand and those guys were so into new technology. Without that fax, California would have lost six rivers.

Alex Steffen: Traditionally, energy was a field in which Exxon types molded the world to their benefit and delivered energy with mass systems. But the WEC championed personal energy - wind power, solar power, and water power. The result is today's explosion in green energy. The best hope we have for solving climate change is exactly what was accelerated by the WEC.

Stewart Brand: We were part of a process that 30 years later means California uses half as much energy as any other state, with 30 percent growth.

Kevin Kelly: The catalog's voice was a breakthrough. There wasn’t a style sheet; they left in most of the spelling and grammar errors. The WEC also had a gossip section. It was about the people who wrote the catalog. Brand was the first person to make gossip a legitimate topic.

Richard Wurman: A West Coast catalog for hippies that won the National Book Award [in 1972, in the Contemporary Affairs category]? It was a paradigm shift in information distribution. In the early '70s, the public didn't know what a yurt was, or where to buy one. But if you were interested in moving back to the land and needed sturdy, cheap housing, this was invaluable information. I think you can draw a pretty straight line from the WEC to a lot of today's culture. It created an aroma that's so pervasive, most people don't even know the source of the smell.

Kevin Kelly: For this new countercultural movement, information was a precious commodity. In the '60s, there was no Internet; no 500 cable channels. Bookstores were usually small and bad; libraries, worse. The WEC not only gave you permission to invent your life, it gave you the reasoning and the tools to do just that. And you believed you could do it, because on every page of the catalog were other people doing it. This was a great example of user-generated content, without advertising, before the Internet. Basically, Brand invented the blogosphere long before there was any such thing as a blog.

Alex Steffen: The WEC is the first expression of collaborative media in the age of mass media. But this idea isn't new; it's at least as old as the Enlightenment. In the 1700s, the French philosopher Denis Diderot did the same thing in his Encylopédie - his great, collectivist attempt to catalog all human knowledge.

Kevin Kelly: Brand is single-handedly responsible for American culture's acceptance of computers. The very first WEC, in between the ads for beekeeping equipment, had an article about a personal computer. It was $5,000, the most expensive thing in the book. In the '60s, computers were Big Brother, the Man. They were used by the enemy: massive, gray-flannel-suit corporations and the government. But Brand saw what was possible. He understood that if these tools became personal, it could flip the world around into a place where people were gods.

John Markoff: There was a very big Luddite component to counterculture back then, but Brand wanted nothing to do with it. He had a military background and a big conservative bent. He really believed you could take the tools of the establishment and use them for grassroots purposes. He was, after all, the guy who coined the term personal computer.

Stewart Brand: I was a scientist, so the idea of being afraid of science boggles my mind. But my military background also made me less paranoid about the government. I was at Stanford in 1963, and I saw a couple of guys in the back of the computer lab just out of their bodies playing Space Wars [the very first video game]. Because of my background, I had no built-in objections. Instead, I was treated to the sight of what was possible when these machines became personal.

John Perry Barlow: Before the WEC came out, business was big and ugly. It was a kingdom of acronyms like IBM and GE. But Stewart saw sustainable small business as a virtue.

Lloyd Kahn: This wasn't business as usual. Backyard tool inventors are a real subculture, usually very apart from the mainstream. For these tool guys, the WEC wasn't just their Bible; it was great advertising. I think we kept a lot of people in business over the years.

Kevin Kelly: The WEC helped rid us of our allergy to commerce. Brand believed in capitalism, just not by traditional methods. He was the first person to embrace true financial transparency. His decision to disclose WEC's finances in the pages of the catalog had a profound ripple effect. A lot of those hippies who dropped out and tried to live off the land decided to come back and start small companies because of it. And out of that came the Googles of the world.

Fred Turner: The WEC set the stage for all of today's social networks. This kind of collaborative communication and the emphasis on small-scale technology really hit home in early Silicon Valley. You have to remember that the first Xerox PARC [the Palo Alto Research Center, a division of Xerox credited with inventing laser printing and the Ethernet, among other things] library consisted of books selected from the WEC by computer guru Alan Kay.

Stewart Brand: Our impact on small business? Well, the Snugli baby carriers took off because we reviewed them early.

Howard Rheingold: Brand united do-it-yourself (DIY) with new utopian society. He really believed that given the right tools, any change is possible.

Peter Coyote: For the fifteen years I lived in a cabin without electricity, the WEC was my invaluable resource of technology - low tech, low impact, and low cost. The whole DIY movement was a nonstarter without the right tools and skills and books. People are scared today, but myself and all my peers aren't afraid of economic collapse. We learned, with the help of the WEC, to take care of ourselves. So if the world goes to shit, all that means is we're going to have to go back to doing what we already know how to do.

Howard Rheingold: For the environmental movement, the WEC was a lens amplifying many individual efforts, from Rachel Carson's Silent Spring to DIY energy to systems thinking. These were all individual ideas before the catalog blended them together, turning them into a cluster that had a far more significant impact.

John Perry Barlow: The WEC had a number of notable spin-offs, the WELL foremost among them. Brand wanted a gathering place for people interested in new technology and he wanted to give those people a more interactive forum than they could get in the magazine. The WELL was it. Pre-Internet, this was the bulletin board for the digerati. It was at the core of the entire Silicon Valley revolution. But because it had such an impact on technology, people forget how far flung its reach was. The WEC also popularized a friendlier way to break horses and new ideas in cattle grazing based on systems ecology. These two things turned ranchers into hippies, and that's a trend that's still going strong.

Jay Baldwin: I remember saying that all this DIY soft-technology was great, but until you could buy mass-produced solar hardware at Sears then we haven't done a damn thing. Well, you can now buy it at Costco. I guess we have arrived.

Stewart Brand: The WEC is extinct. But right now on my belt I've got a really great Nikon monocular that can read a bug's expression from 4 feet away; a sheaf knife, in case I need to lop off a weed in the garden; my favorite Swiss Army knife (the long kind); my Trio, a descendant of the personal computer; and a set of DIY bifocals. The catalog's slogan was "Access to Tools," and these are some pretty cool tools.

Huey Johnson, the secretary of resources for the State of California from 1978 to 1982, received the President's Award for Sustainable Development in 1996. He founded the Resource Renewal Institute and the Trust For Public Land (now America’s fifth-largest environmental organization).

Jay Baldwin, an industrial designer, worked in the California Office of Appropriate Technology under Governor Jerry Brown and in the '90s at Amory Lovins' Rocky Mountain Institute, where he helped develop the ultra-efficient Hypercar. He previously served as design editor for the WEC.

Actor Peter Coyote cofounded the anarchist group the Diggers in the '60s and worked with the San Francisco Mime Troupe before going on to Hollywood. His films include Bitter Moon, Erin Brockovich, ET, Jagged Edge, and Kika.

Steve Jobs is the cofounder and CEO of Apple Inc. He also ran Lucasfilm Ltd and Pixar Animation Studios from 1986 to 2006. In 2007, Fortune listed him as its Most Powerful Businessman.

John Markoff is a senior writer with The New York Times and the author of What the Dormouse Said: How the 60s Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry.

Andrew Kirk is the author of Counterculture Green: The Whole Earth Catalog and American Environmentalism.

John Perry Barlow grew up a Wyoming cattle rancher and later became a lyricist for the Grateful Dead. In 1990, he cofounded the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which promotes freedom of expression in digital media. He is a fellow at Harvard Law School's Berkman Center for Internet and Society.

Larry Peterson is presently the special advisor for energy and sustainable planning at Kitson & Partners.

A staff member in former Oregon governor Tom McCall's office in the late '60s and early '70s, Vera Marcus was the third African-American student in America to attend an integrated high school (her older sister was the first). She went on to work extensively with Huey Johnson when he was secretary of resources for California. She now practices law in Northern California.

Alex Steffen cofounded the environmental weblog worldchanging.org and serves as the site's executive editor and CEO. He also edited the last, unpublished WEC.

Kevin Kelly is the founding executive editor of Wired magazine and a former publisher of the WEC. Alongside Brand, he helped launch the WELL (Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link), an early, hugely influential online community. Many people feel his website, Cool Tools, is the modern incarnation of the WEC.

Fred Turner is currently an assistant professor in the communications department, among other positions, at Stanford University. He is the author of From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism.

Lloyd Kahn's early work building sod-roofed homes, geodesic domes, and other alternative structures caught Brand's attention. He went on to form Shelter Publications, one of the first West Coast publishing houses.

Richard Wurman, an American architect and graphic designer, has written more than 80 books, founded the Technology Entertainment Design (TED) conference, and is credited with coining the term information architect.

Stewart Brand went on to found or cofound a number of organizations, including the Global Business Network (a scenario consultancy service) and the Long Now Foundation (an institution that fosters responsible long-term thinking). He has also written four books and is presently at work on another, tentatively titled Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto. He lives with his wife, Ryan, on a 62-foot tugboat named Mirene in Sausalito, California.

Copyright Environ Press 2008